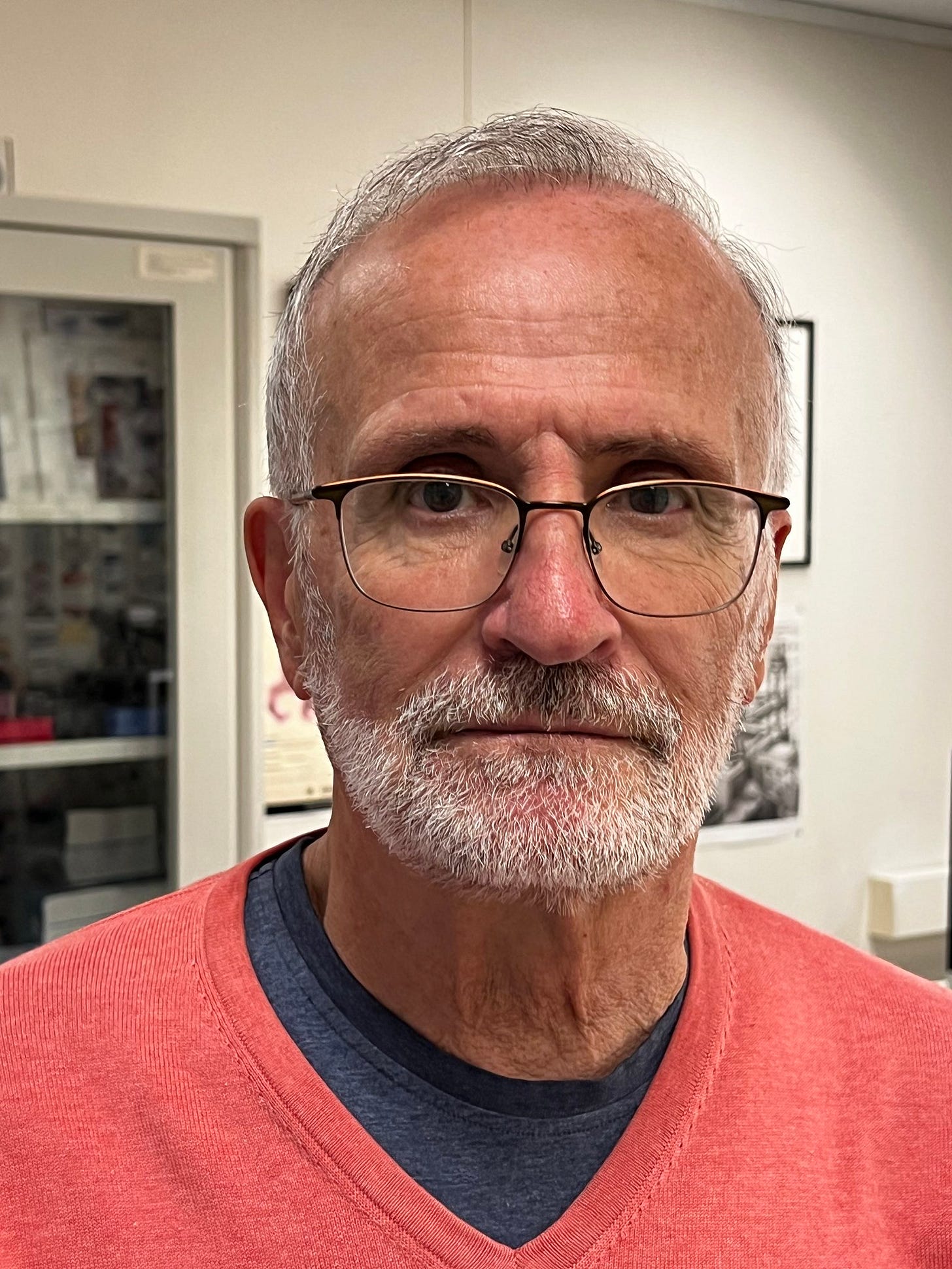

🤖🧠 Ramon López de Mántaras: "If you're looking for truthful information, forget ChatGPT" ❌

Spain's AI pioneer debunks tech marketing hype and the (not-so-near) arrival of AGI.

Check out this exclusive interview with Ramon López de Mántaras, one of the founding fathers of AI in Spain and Catalonia! 🤖 This is a highly relevant conversation for understanding the origins of AI in Spain. There's also a video in Catalan! 👇

Here's the full interview with Ramon López de Mántaras for the Transparent Algorithm newsletter, issue number 86.

Ramon López de Mántaras i Badia (Sant Vicenç de Castellet, 1952) is an electronics engineer who studied in Mondragón, Toulouse, and Berkeley. Upon returning to Spain, he pioneered groundbreaking research in AI. He has met all the leading figures in global AI and is now highly critical of how this technology is being promoted.

Could we say you are one of the pioneers of AI in Spain? Possibly, because I started my doctoral thesis in artificial intelligence in Toulouse in 1974 and finished it in 1977. In 1974, even though I was in France, there were very few people doing AI. We could say I'm among the first to do AI in Europe. In fact, my thesis, in which I introduced two new probabilistic learning algorithms for an anthropomorphic robotic hand to learn to recognize objects solely from tactile sensor data, I defended it in 1977, and it was one of the first 4 or 5 theses on AI applied to robotics done in France.

And among the first in Europe. At that time, perhaps around a dozen theses on AI applied to robotics had been done in Europe.

What year was your first publication? June 1976, at a conference in Sweden. It's one of the first works on machine learning in Europe: an algorithm for self-learning for the classification and recognition of vectorial patterns. Objectively, I was among the first to work on machine learning in Europe.

Among Spaniards and Catalans, definitely one of the very first. After France, I went to Berkeley and specialized in artificial intelligence because while I was in Toulouse, there was already a lot of activity in the field called Pattern Recognition, but at that time, it wasn't yet included in what we now call AI. In my thesis, the algorithms I invented did tactile pattern recognition. Almost no one had done that. Everyone was doing pattern recognition based on artificial vision. In the United States, there were specialized conferences on pattern recognition, and AI conferences had only recently started, since the late 60s or early 70s. In Europe, AI wasn't talked about much; it was very unknown. When Professor Lotfi A. Zadeh [creator of fuzzy set theory and fuzzy logic] came to Toulouse, he gave a conference on AI.

Is that the first time you heard about AI? It was the first time I heard about artificial intelligence properly. It was in 1975 in Toulouse. I thought: "This is very similar to what I'm doing with my thesis." I defended it in 1977. Zadeh explained that one of the things done in AI is machine learning, making machines learn. My thesis was about that! It turned out I was working on a topic that, especially in the United States and Scotland, in Edinburgh, because they were very pioneering, was artificial intelligence. Very enthusiastic about all this, I spoke with Lotfi Zadeh [1921-2017] and he encouraged me to apply to the University of Berkeley for a master's in AI under his supervision.

What year did you go to Berkeley? November 1977. Thesis and wedding in Toulouse, and in the fall, off to the United States. I was there until the end of 1979. I did a research master's, meaning fewer courses but I had to do a thesis.

What was that thesis about? I did an extension of the first one on learning but already introducing concepts of something called fuzzy logic. I developed a new learning algorithm that incorporated models based on this logic. When I came back here, I spent a year teaching and researching in Mondragón in the computer science department that had just been founded at the Ikerlan technology center, in 1979. And at the end of 1980, at the UPC, they needed professors because the computer science degree was starting. It was, along with San Sebastián and Madrid, one of the first three universities that started the computer science degree in Spain, and I joined as a professor. I defended my doctoral thesis at the Faculty of Informatics of Barcelona in 1981. At that time, it was faster to do another thesis than to validate the one I had from France! It was the first doctoral thesis in computer science in Catalonia, and I wrote it in Catalan. At the national level, it was one of the first two or three theses in computer science.

Did the political context of the transition affect a Catalan researcher like you? I left Spain, but not for political reasons. At that time, Toulouse was already recognized as a technologically advanced place. There was the entire aerospace industry, the Airbus. There was a high level of electronics, computer science, and automation. And the United States was obviously the Mecca of artificial intelligence. I went to learn in the best places. The University of Berkeley is one of the most prestigious in the world.

And when you return during democracy? I had done all my training in Spanish and wanted to teach in Catalan. I went to intensive Catalan classes to be able to write on the blackboard without making mistakes. I didn't want to find myself with 18-year-old boys and girls trained in Catalan and me making mistakes.

How old were you? When I returned from the United States, I was 27. And at 28, I started teaching at the Polytechnic, which was then called the Polytechnic University of Barcelona.

"I'm very critical of the anthropomorphization of AI, and they want to sell us the idea that human-level General AI is just around the corner."

Since then, have you experienced a great winter in relation to AI? I have lived through one, and another very mild one. There was a winter that coincided with my return from the United States. In the mid-80s, expert systems, which tried to emulate the knowledge of a human expert in a very specific and limited topic, such as the diagnosis of outpatient pneumonia in adults, for example, could perform very deductive reasoning. They boomed, but they had a problem: they didn't evolve, they didn't learn. There was a first winter, which we didn't suffer much here because precisely Enric Trillas, who supervised my thesis in Catalonia, was appointed president of the CSIC in 1984. And in 1985, he proposed to me to create an artificial intelligence department at the Centre d'Estudis Avançats de Blanes, with Jaume Agustí, from the Autónoma. Therefore, when in the United States and England they noticed a negative impact, a winter, here, on the other hand, due to Enric Trillas's initiative in the CSIC, we had support.

A spring. It's curious. You go against the grain. In those years, the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science also began to finance research projects. An organization was created to launch the first calls for projects. We applied in 1985 and got a project to work with AI in Blanes. We were lucky that Spain was starting to get serious about research and that Enric Trillas was president of the CSIC.

It's the arrival of the socialists. Felipe González had recently won the elections.

Who was the minister? I'll tell you now [Types on his laptop and searches online.]

Why don't you ask ChatGPT? Because I don't trust factual things. It can invent facts. That's why Google is much better.

Is traditional internet search more efficient than conversational AI queries? If you want information with guarantees of truthfulness, forget about ChatGPT. Absolutely! About me, it mentions works I've never published. It invents titles and my birthplace. Just a few days ago, a colleague even told me that, according to ChatGPT, I passed away last year!

But now you have the search mode within ChatGPT. Yes, but even so, it doesn't do it well!

Are you sure? OpenAI's O3 and Anthropic's Claude search Google or Wolfram. They search externally, incorporate it, and tell you. Despite that, they don't verify. They just dump it in.

But doesn't AI have a greater ability to cross-reference sources than you searching on Google right now? They could have the capability, but for some reason, they don't do it well. I don't trust them. Look: José María Maravall, from 1982 to 1988, Minister of Education and Science.

With the socialists, did things change? They took over and said: "We have to make it possible for the academic world to submit research proposals that can be evaluated and funded if they are good." We caught that moment.

A local spring. Yes, but not only for AI but for science in general. Before the 80s, there were no calls for proposals in all fields of knowledge.

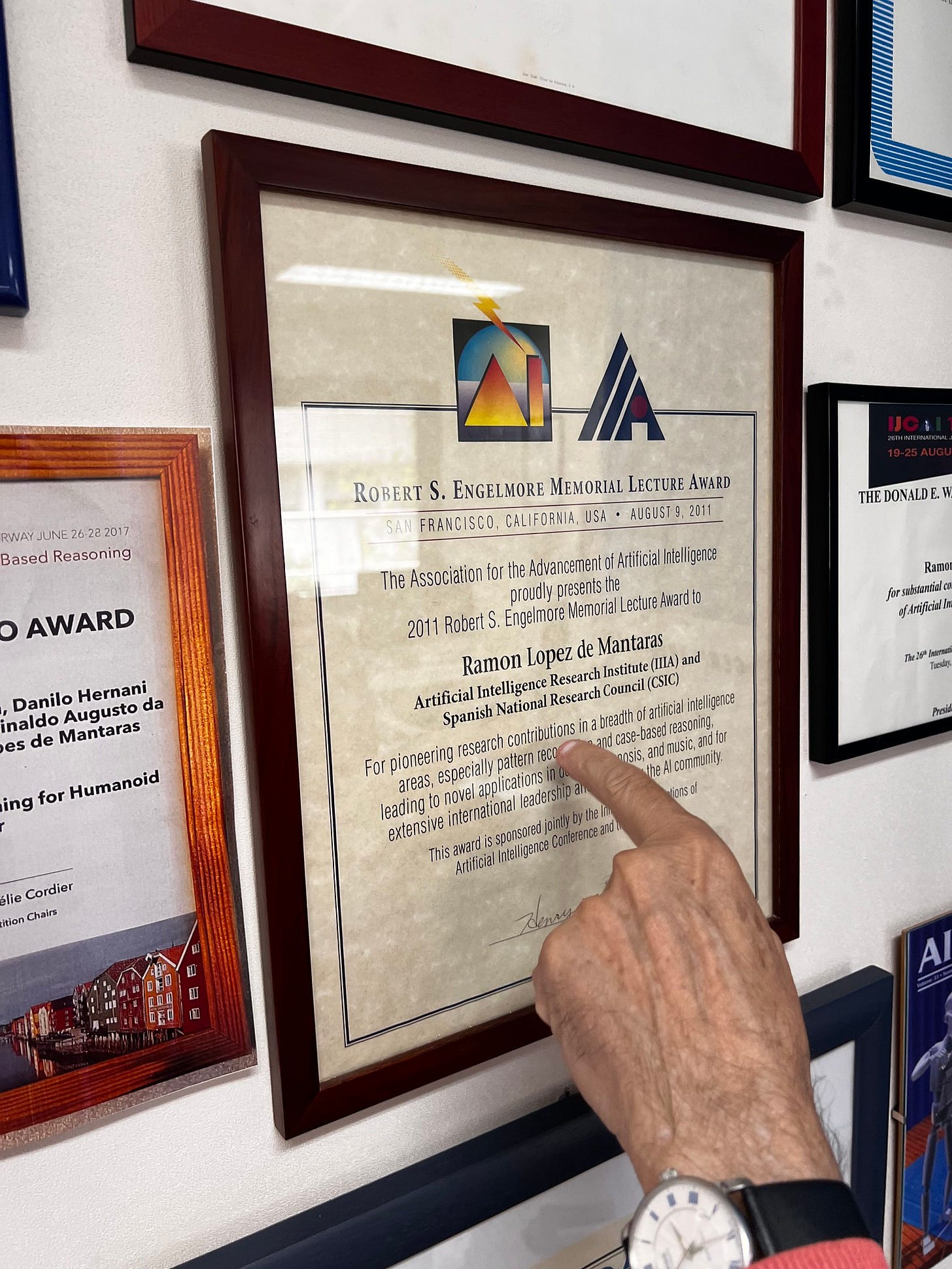

Which AI projects do you remember? Learning and expert systems. In 1987, along with Carles Sierra, our colleague Lluís Godó, and Dr. Albert Verdaguer, we received the European AI prize for the best work in all of Europe. It was in the medical field. Inductive symbolic learning, not probabilistic or neural networks, was what was most worked on then. In the 80s, neural networks didn't have a very good reputation.

What came next? Bayesian networks or probabilistic graphical models. This had a very strong impact in the late 80s. It comes from Judea Pearl, from the University of California, Los Angeles. I know him very well.

Of the AI giants, which ones have you met? All of them. Most of them. Marvin Minsky and I became friends.

John McCarthy? Of those who were at the Dartmouth Convention [where the concept of artificial intelligence was coined in 1956], I met Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, and Oliver Selfridge. All three are deceased.

And of the living ones? Judea Pearl, Stuart J. Russell... all of them. Of the living ones, all.

Who impressed you the most? [Thinks] Minsky. He's also the one I interacted with the most. We met in 2006, when it was 50 years since Dartmouth. I gave the opening lecture at the German Artificial Intelligence conference. Marvin Minsky was at the presidential table of the conference. I talked about a system of analogy-based reasoning applied to the generation of expressive music. Minsky was a pianist and knew a lot about music. He liked my lecture because analogy-based reasoning is cognitively plausible. He was very critical of AI approaches that deviated from being cognitively plausible, which means they bear a certain relation to human intelligence. Humans often solve a new problem not from scratch, but by taking advantage of the fact that this problem has similar characteristics to previously solved problems from the past. We leverage problems we've already solved to solve new problems more easily and quickly. I talked about this in the application to music. Since Minsky was passionate about music, it was perfect.

So, was it revolutionary back then for a machine to understand the logic of human reasoning? We were awarded the world's most important prize in computer music, the Swets & Zeitlinger in 1998. We were the first to get an AI to generate music with expressiveness. Not just boring, neutral, mechanical sounds, but music with crescendos, diminuendos, playing with articulation, the attack of notes... We were among the first to incorporate 5 expressive variables in music synthesis.

What's your reaction when you hear a song created with Suno or Udio? They are very good at imitating an existing style, but they cannot break rules. They are not creative.

You wouldn't be surprised? No, because they don't break rules.

Is AI still predictable? Yes, because it's trained on everything that already exists.

And what happened in the 90s? It's the boom of machine learning, of making machines learn. And there's also a boom in neural networks.

Who is the father of the resurgence of neural networks? The backpropagation algorithm, which allows multi-layered neural networks to learn, to converge. One of the fathers is Geoffrey Hinton.

Hinton is very critical now. Critical in his own way and, from my point of view, for erroneous reasons. Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton are the godfathers of deep learning.

"We were the first to make an AI generate music with expressiveness."

What were you doing in the 90s? In 1991, I developed a new algorithm that allowed selecting the best attributes to build a decision tree. It enables prediction with classification algorithms based on the values of certain attributes. It was a completely new attribute selection method that improved on previous ones. It's all symbolic, not probabilistic.

It infuriates you when people talk about AI hallucinations. Yes, because we are anthropomorphizing AI. There are no hallucinations, there are just errors.

I see you're very critical. I am very critical of the anthropomorphization of AI, and that they want to sell us the idea that human-level General Intelligence (AGI) is just around the corner.

Is it due to marketing? Mainly the marketing of big tech companies that set the pace. It's also true that academic results sometimes have communication departments that produce exaggerated headlines.

Are some of the culprits also scientists who have gone to work for big tech companies? Some of those too.

When do you think AGI will arrive? There's a problem with AGI: there are 20 different definitions.

Are large language models a problem? Regarding the fact that we anthropomorphize them, yes, that's a big problem. But used wisely, they can be useful. You can find concrete applications that save you work.

If you write with these large models, an alterity arises: it's no longer you. When I used ChatGPT to translate, I felt like it wasn't me. I couldn't translate my book because it's not the way I write. That's the point. We have to make an effort to be ourselves.

Now, with AI, we have to make that effort more than ever. That's right. "The process of writing generates ideas and thoughts that we wouldn't otherwise have and, therefore, improves our cognition (...) When we spend less time writing, our cognitive system develops less, which can impoverish our general cognitive abilities," says an article I use in my presentations. Writing is thinking.

Most people think little, read less, and don't write... That's all we needed. You remove incentives for them to do it. Those who do it are cheating themselves. The student who uses ChatGPT is deceiving themselves.

Cheat sheets always existed. Yes, but to make a cheat sheet, you had to make a cognitive effort to summarize and put it on paper or your hand. ChatGPT is less elaborate and enriching than the old-fashioned cheat sheet. Let's be careful about what we're doing with AI.